Students trust their institution to use AI ethically, but remain firmly committed to human connection for complex academic challenges.

Executive Summary

As artificial intelligence tools become increasingly integrated into higher education, understanding student attitudes toward these technologies is critical for administrators making decisions about AI implementation. This brief examines student perspectives on AI trust, preferences for human versus AI support, and comfort with AI-mediated interactions in their educational experience.

In September 2025, we surveyed 545 students at Western Governors University about their attitudes toward AI use in education, their trust in various stakeholders to use AI responsibly, and their preferences for human versus AI support. In our full report, we explore data around professional and social capital, specifically within the adult online learner experience.

In this brief, we explore a subset of the survey, specifically four questions that were created by reporters Ashley Mowreader from Inside Higher Ed and Alcino Donadel from University Business to explore additional areas of the student experience.

The four questions explored specifically in this research brief include:

- I trust WGU staff members to use AI ethically and responsibly

- I trust WGU staff members to use AI ethically and responsibly

- I often turn to chatbots (like ChatGPT) instead of reaching out to WGU staff or faculty for help.

- I prefer getting feedback from AI tools like ChatGPT over feedback from my instructors

The results reveal complex attitudes that point to both opportunity and caution for institutions designing AI-enabled student support.

Key Findings:

- High institutional trust, lower peer trust: While 65% of students trust WGU staff to use AI ethically and responsibly, only 50% trust other students to do the same, a 15-percentage-point trust gap.

- Human connection wins for complexity: When something is complex, 76% of students prefer help from a person over AI, and 89% say they can tell the difference between a bot and a person.

- The AI user divide: Regular AI users are significantly more comfortable with AI-mediated interactions than occasional users or non-users, but even frequent users prefer human instructors for feedback.

- Students know how to escalate: 65% of students know how to escalate an issue from a bot to a person, though comfort varies significantly by AI usage patterns.

- Mixed signals on chatbot adoption: While 46% of students disagree that they often turn to chatbots instead of staff or faculty, 33% agree they do, suggesting emerging but not universal adoption.

These findings reveal a critical insight for administrators: students are not resistant to AI in education, but they are selective about when and how they use it. They demonstrate high trust in institutional AI use while maintaining a strong preference for human connection when navigating complex academic challenges. For institutions implementing AI tools, these results underscore the importance of positioning AI as a complement to (not a replacement for) human support.

Introduction

Generative AI has rapidly moved from experimental technology to everyday tool in higher education. Institutions are deploying AI-powered chatbots for student support, exploring AI-assisted tutoring, and considering how these tools might scale personalized learning. Yet as administrators decide where and how to integrate AI, a critical question remains: What do students actually want?

Previous WGU Labs research has shown that while AI awareness and usage have grown among students, many lack confidence in their ability to use these tools effectively, and significant equity gaps persist in AI access and adoption. Faculty surveys have revealed that educators are uncertain about AI's role in teaching and learning, with mixed feelings about both its potential and its risks.

This brief contributes to that body of knowledge by examining student attitudes toward a different dimension of AI in education: trust. Specifically, we explore who students trust to use AI ethically, when they prefer human versus AI support, and how comfortable they are with AI-mediated interactions in their educational experience.

These questions emerged from a larger survey on professional networking and peer connections among WGU students. While the primary focus of that research was on social capital and relationship-building, we included several questions about AI attitudes to understand how students view technology as they navigate their education. Those findings—presented here—reveal important insights about student preferences that can inform institutional AI strategy.

Methodology

We distributed this survey in September 2025 to examine professional networks, social connections, and attitudes toward AI among adult working students at Western Governors University (WGU). The survey included items on AI trust, preferences for human versus AI support, comfort with AI-mediated help-seeking, and usage patterns of chatbot technologies.

Participants were recruited from the WGU Student Insights Council, a standing panel of approximately 6,000 students representative of WGU's overall student population of roughly 194,000 students. The panel reflects key demographics including program of study, degree level, and first-generation college status, with intentional oversampling of Asian, Native American/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander students to enable more reliable subgroup analyses.

Overall, 545 students responded to the survey. Respondents came from all four WGU colleges: School of Education (33%), School of Business (27%), School of Technology (23%), and Leavitt School of Health (16%). The sample was predominantly female (79%), with a mean age of 35.8 years. Sixty-eight percent identified as White, 18% as Black, 11% as Latino/a/x, and 10% identified with two or more racial or ethnic groups. Half (50%) were first-generation college students.

For analysis, we segmented respondents by their self-reported AI usage: regular users, occasional users, and non-users. This allowed us to examine how familiarity with AI tools shapes attitudes and preferences.

Key Findings

Key Takeaway 1: Students trust their institution to use AI ethically, but trust in peers is significantly lower

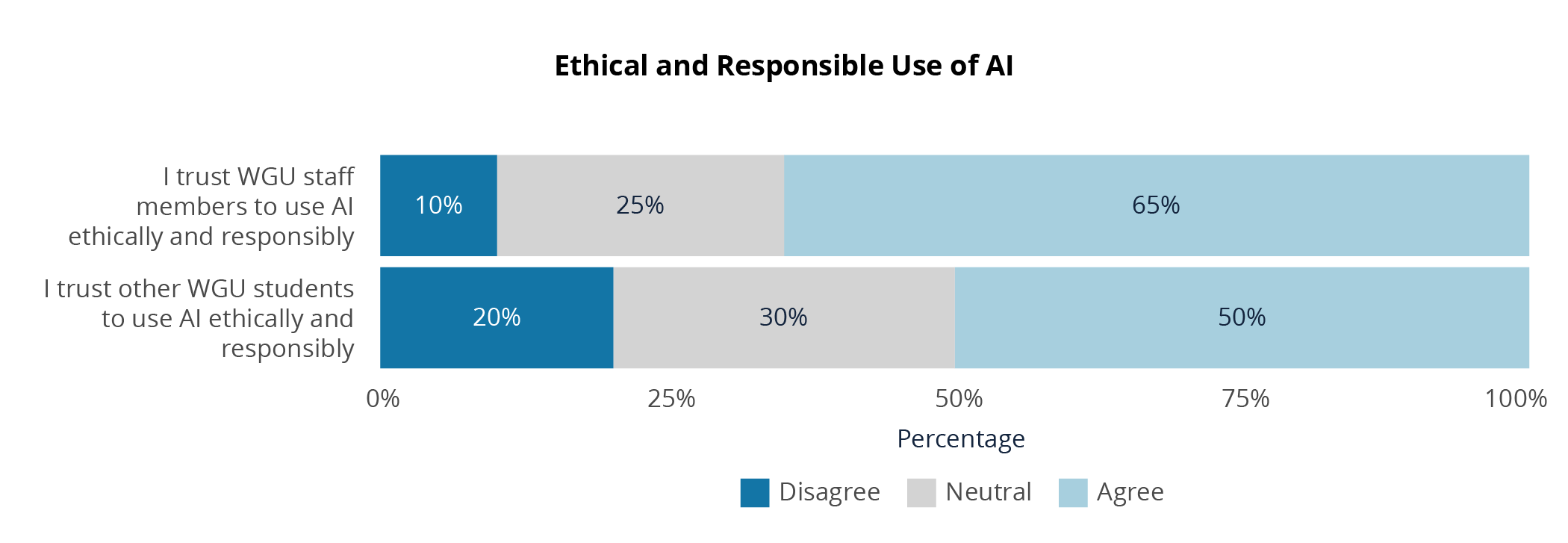

When asked about trust in AI use, students showed notably higher confidence in institutional actors than in their fellow students. Sixty-five percent agreed that they trust WGU staff members to use AI ethically and responsibly, compared to just 50% who said the same about other WGU students, a 15-percentage-point gap.

This trust differential suggests that students view institutional AI use through a lens of professional responsibility and accountability. Staff members, including faculty and administrators, are seen as having clearer ethical guidelines, stronger oversight, and more at stake when using AI in their work. In contrast, peer AI use may feel less regulated and more unpredictable.

Interestingly, only 10% of students disagreed that they trust staff to use AI ethically, while 20% disagreed when asked about trusting other students. This suggests that skepticism about peer AI use is more pronounced than concerns about institutional adoption.

Why This Matters

This trust gap has important implications for how institutions communicate about AI implementation. Students appear ready to accept AI tools when deployed by the institution itself for advising, tutoring, administrative support, or assessment, as long as they believe those uses are governed by clear ethical standards.

However, the lower trust in peer AI use suggests potential concerns about academic integrity and fairness. If students worry that classmates might misuse AI tools (for example, to complete assignments dishonestly), institutions must be proactive in setting clear boundaries, teaching responsible AI use, and creating cultures of academic honesty that extend to emerging technologies.

This finding also highlights an opportunity: by demonstrating ethical AI use at the institutional level, universities can model responsible practices for students and build broader comfort with these tools across the academic community.

Key Takeaway 2: When things get complex, students overwhelmingly prefer human help

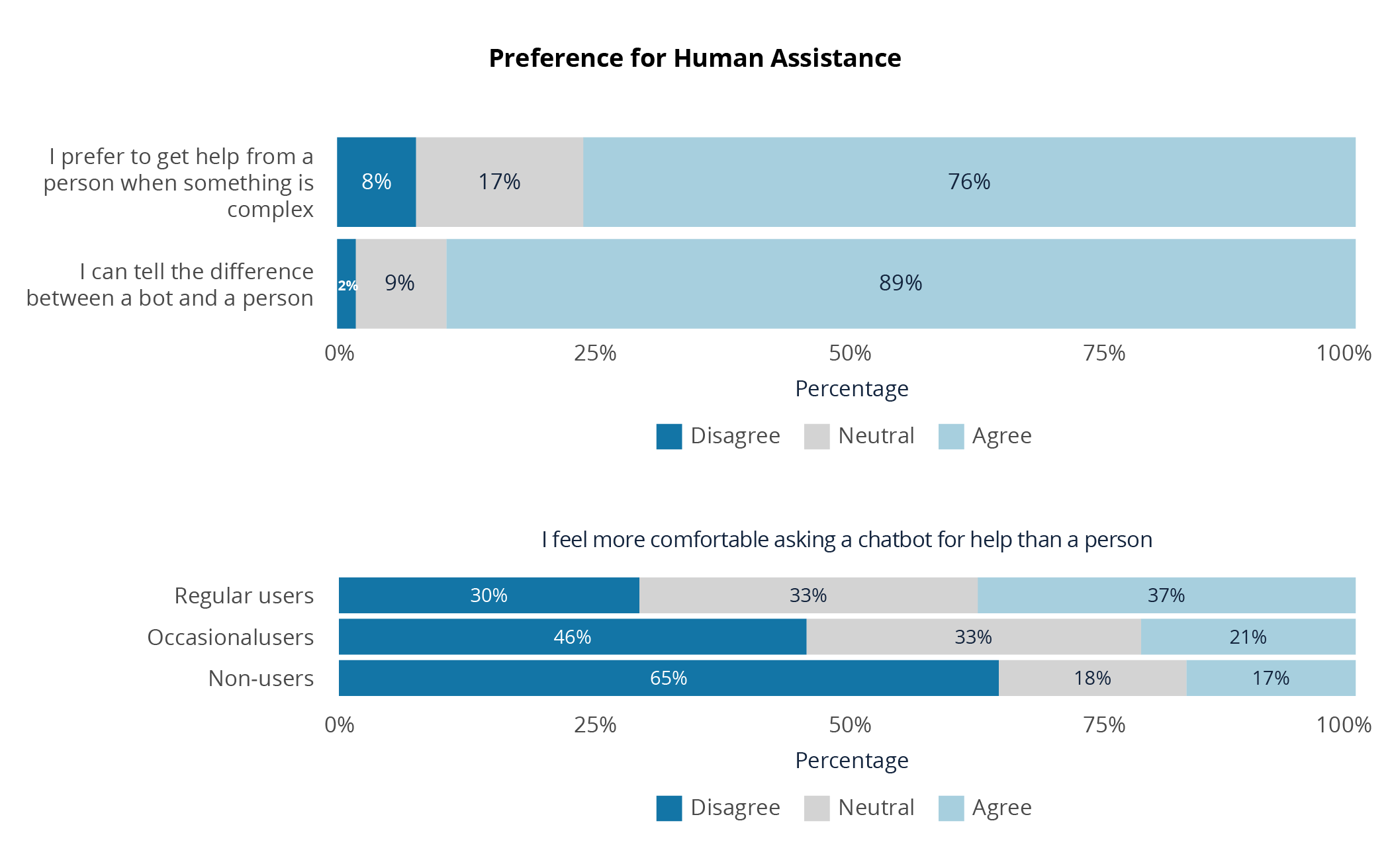

Despite growing familiarity with AI tools, students continue to prefer human support when facing complex challenges. Seventy-six percent agreed that they prefer to get help from a person when something is complex, with only 8% disagreeing.

This preference for human connection aligns with other findings in our research: students value institutional belonging and support, and they see people as their primary source of help when the stakes are high or problems are nuanced.

Students also demonstrated confidence in their ability to distinguish between human and AI interactions. Eighty-nine percent agreed that they can tell the difference between a bot and a person, suggesting that most students are not easily fooled by AI-mediated support systems and can recognize when they're interacting with technology versus a human being.

However, comfort with AI interactions varied significantly by usage patterns. Among regular AI users, only 30% disagreed that they feel more comfortable asking a chatbot for help than a person. But among non-users, that number jumped to 65% indicating that familiarity breeds comfort, while unfamiliarity reinforces preference for human interaction.

Why This Matters

These findings suggest that AI should be positioned as a first-line support tool for straightforward questions (e.g., course logistics, deadline reminders, navigating the student portal) but not as a replacement for human advisors, mentors, or faculty when students face complex academic or personal challenges.

The fact that 89% of students can tell the difference between bots and humans also means institutions cannot "hide" AI interactions or assume students won't notice when they're chatting with a machine. Transparency about when and how AI is being used will be critical for maintaining trust.

For administrators, this means designing support systems that use AI to triage and handle routine inquiries while ensuring students have clear, easy pathways to reach a person when they need more nuanced help. The goal should be to free up human staff time for high-touch interactions, not to eliminate those interactions altogether.

Key Takeaway 3: Students prefer feedback from instructors, even when AI offers an alternative

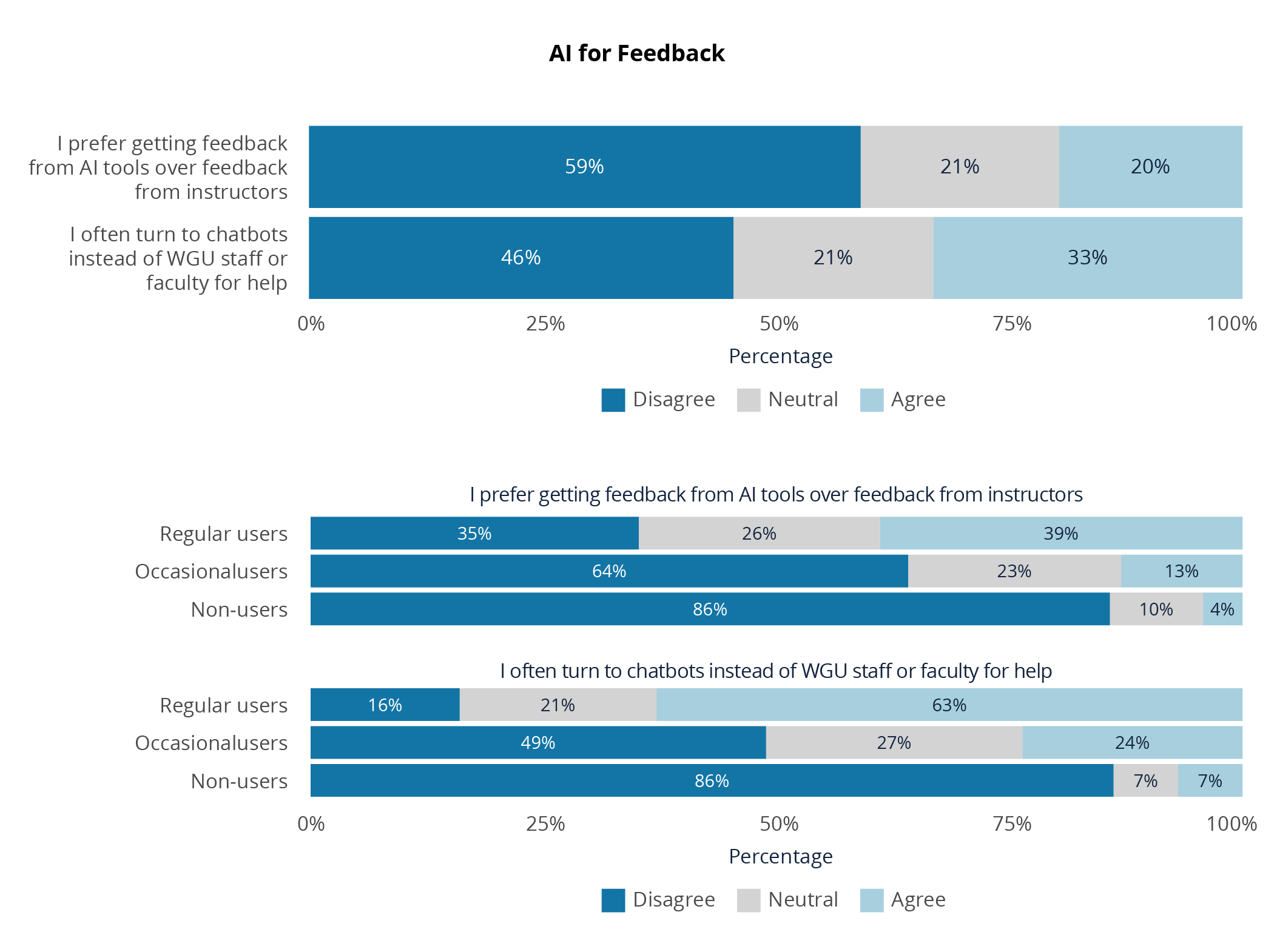

One of the most striking findings from our survey is that students do not want AI to replace instructor feedback on their work. When asked whether they prefer feedback from AI tools like ChatGPT to feedback from their instructors, 59% disagreed — more than twice as many as the 20% who agreed.

This finding held even among regular AI users, who might be expected to embrace AI-mediated feedback. While regular users were somewhat more open to the idea than non-users, the majority still preferred human instructor feedback over AI-generated responses.

Similarly, when asked whether they often turn to chatbots instead of reaching out to WGU staff or faculty for help, 46% disagreed, while 33% agreed. This suggests that chatbots are being used by a meaningful subset of students, but they are not yet displacing human support as the default option.

Why This Matters

This finding offers important reassurance to faculty and administrators concerned about AI eroding the student-instructor relationship. Students are not looking to replace their professors with chatbots. They value human feedback, especially on substantive academic work, and see instructor input as qualitatively different from what AI can provide.

For institutions, this means AI tools are best positioned as supplements to instructor feedback, rather than replacements. AI might help students brainstorm ideas, check grammar, or troubleshoot technical problems, but it should not be framed as equivalent to personalized, expert feedback from a human instructor who understands the student's learning trajectory and can offer context-specific guidance.

That said, the 33% of students who report turning to chatbots rather than staff or faculty represent a significant and growing user base. Institutions should examine why students are choosing AI over human assistance in these cases. Is it convenience? Speed? Perceived lower stakes? Understanding these motivations can help schools design better support systems that combine the best of both human and AI assistance.

Key Takeaway 4: AI familiarity shapes comfort, but doesn't eliminate human preference

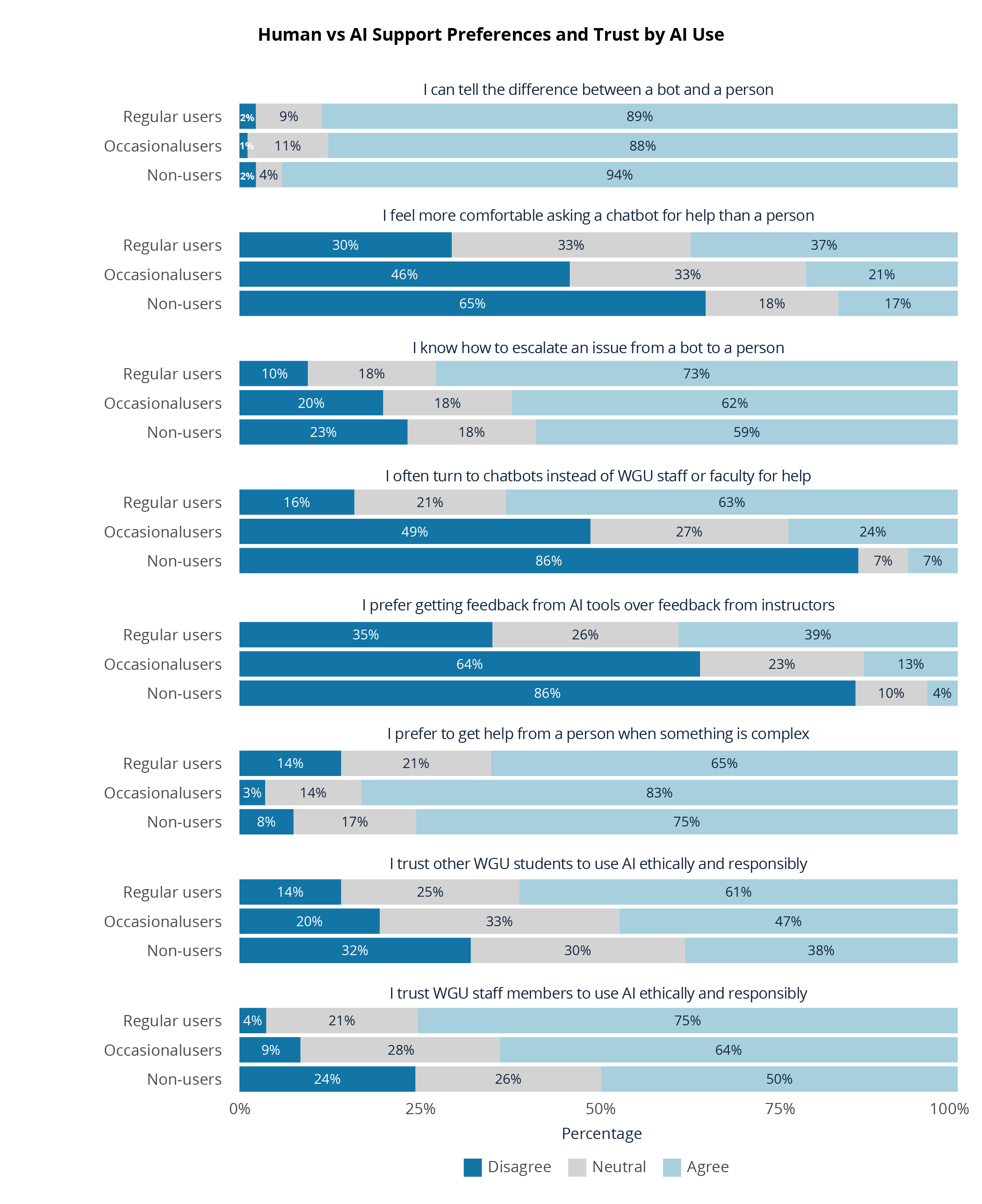

Throughout our analysis, we found that students who regularly use AI tools demonstrate different attitudes and behaviors than occasional users or non-users. Regular users were more comfortable interacting with chatbots, more likely to report using them for help, and less insistent on human-only support for complex problems.

For example, 63% of regular AI users agreed that they often turn to chatbots rather than to WGU staff or faculty, compared to 24% of occasional users and 7% of non-users. Similarly, 37% of regular users said they feel more comfortable asking a chatbot for help than a person, compared to 21% of occasional users and 17% of non-users.

However, even among regular users, preferences for human support remained strong in certain contexts. Regular AI users still preferred instructor feedback over AI feedback and still valued human help for complex challenges. What shifted was not the elimination of human preference, but an expansion of comfort with AI as an additional support option.

Perhaps most notably, regular users were better equipped to navigate hybrid human-AI support systems. Seventy-three percent of regular users knew how to escalate an issue from a bot to a person, compared to 62% of occasional users and 59% of non-users.

Why This Matters

These findings suggest that as students gain experience with AI tools, their comfort and willingness to use them increase, but their fundamental preference for human connection in high-stakes or complex situations remains.

For institutions, this means that AI literacy and familiarity matter. Students who understand what AI can and cannot do, who have used these tools successfully, and who feel confident navigating them are more likely to embrace AI-assisted support systems. Conversely, students with limited AI exposure may resist or underutilize these tools, potentially widening existing equity gaps.

Institutions should consider offering brief AI orientation or training modules that help students understand when and how to use AI tools effectively, how to critically evaluate AI-generated responses, and when to escalate to human support. Building this competency will help ensure that AI tools serve all students, not just those who arrive with prior experience.

Conclusion: AI as Complement, Not Replacement

The findings from this survey paint a nuanced picture of student attitudes toward AI in higher education. Students are not resistant to AI; they trust their institutions to use it ethically, they recognize its utility for certain tasks, and a growing number are incorporating AI tools into their own help-seeking behaviors. But they are also clear about boundaries: they want human connection for complex challenges, they prefer instructor feedback over AI-generated responses, and they value transparency about when they're interacting with technology versus people.

For administrators making decisions about AI implementation, these insights offer important guidance:

- Position AI as a complement to human support, not a replacement. Students see value in AI for routine inquiries, quick answers, and initial triage, but they still want access to people when issues become complex, personal, or high-stakes. Design support systems that use AI to handle straightforward questions while preserving human capacity for deeper engagement.

- Model ethical AI use at the institutional level. Students trust staff and faculty to use AI responsibly. By demonstrating transparent, ethical AI practices by communicating clearly about when and how AI is used, establishing guardrails for appropriate use, and showing how AI supports (rather than replaces) human judgment, institutions can build confidence and model responsible behavior for students.

- Teach AI literacy as a core competency. Students who regularly use AI are more comfortable with AI-mediated support and better able to navigate hybrid systems. Offering training on how to use AI effectively, evaluate AI outputs critically, and escalate to human help when needed will ensure equitable access to these tools.

- Preserve the student-instructor relationship. Students do not want AI to replace their instructors, and they especially value human feedback on their academic work. Institutions should resist the temptation to use AI as a cost-saving measure that reduces faculty contact time or replaces personalized feedback. Instead, AI should free up instructors to focus on the high-value interactions that students care most about.

As AI continues to evolve, student attitudes will likely shift as well. But the core insight from this research remains: students want technology that enhances human connection, not technology that replaces it. For institutions committed to supporting student success, the path forward is clear: use AI strategically, transparently, and always in service of the relationships that matter most.